the conversion

may 2024

It was a shrine to Matisse, the Bauhaus, and rotting bell peppers; it was a dark place, windowless, plastered with fading paint streaks and children’s drawings of wild boars, and everywhere strewn with old newspapers delivering the latest words of Xi Jinping alongside ginseng herbal remedies; it was a fire hazard; it was a ritual I performed from childhood until the year I left for college.

It was an art studio located at the junction where California Highway 85 abruptly gives way to quiet suburban lawns, nestled between an insurance company and an after-school enrichment center (both of which I had never seen populated), on the second floor of a multi-purpose business center. When I was nine, my parents recommended that I start at this studio. They had heard about its focus on the fine arts and ability to produce award winners; in contrast, the classes I had been taking consisted of afternoons spent at a local woman’s kitchen table where she had me copy scenes of tulips and cartoon cats from her archive of wall calendars.

The studio was ruled by Fang Yunhua, a man I guessed to be in his fifties or sixties, with greying hair, wiry patches of mustache, and fingernails perpetually blackened by charcoal dust—features altogether rendering him somewhat ferretlike. Over the years, I learned pieces of Fang’s past, but never enough to piece together a life story or understand his many mysteries. For one, he was ostensibly rolling in cash, but I watched him wear the same olive-colored cargo pants and black trenchcoat and eat the same chicken-flavored Top Ramen every week for nine years. He kept his used dishes in the sink; the piled-high pots and bowls doubled as still life subjects for graphite and charcoal sketch students. Sometimes I gifted him fruit for the holidays; he would wait for them to begin rotting or sprouting mold before putting them out as still life subjects. They are so much more special this way, he would say. He had once served in the People’s Liberation Army, and also studied printmaking at art school. He had been adopted. He was not married to or otherwise in a relationship with his assistant-slash-substitute-teacher Ms. Zhou, but it was rumored that they lived together. She chided him often and managed his finances.

An old photo from Fang's website, when he was younger. He is the fourth from the left, and Ms. Zhou is the third from the left. I am not present in this picture.

My relationship with Fang began as resentment. His criticism was unrelenting and seemed, at times, a puzzle filled with so many contradictions that it was impossible to win. Everything I created was in some kind of transgression. In my first year, the decree on the majority of my work was “too light,” meaning I had not used enough force with my colored pencils, and thus not rendered enough vivid color and value. The punishment for too light was a few example strokes, in Fang’s ideal saturation, scrawled over my piece as a guiding example. I was heartbroken the first time it happened, as I watched him decapitate my carefully-rendered teddy bear. The next stage of failure was “too sweet”—what others might call saccharine—rainbows, cartoons, circles too round, or anything resembling corporate art. Most dreadfully, one could be told that her work was“too same.” (Aside: Fang spoke Mandarin almost exclusively; the few English words he used formed a sort of studio dialect. I remember seeing a white student only once; I translated for her throughout the lesson; I did not see her again.) Too same was a broad and damning category. A piece could be too same if two major forms occupied the same width or height, or if two areas of negative space were too similar, or if there were two clusters with the same number of objects, or this, or that. The trouble was that it felt inevitable to find two areas of the same size in any composition: I could move one problematic line to enlarge a shape, but that would only create several smaller shapes that began to converge. Once, I finally did it: I drew a deserted railway station in front of desert hills; each lateral strip of space unique in dimension and character. I presented it to Fang. He looked. He held it up for the rest of the class to see. “There is nothing wrong with this,” he said, “except that it is boring.”

Ritual demands commitment, and for this one, I woke up at 7 am on Saturdays, eyes closed, barely registering my surroundings in my practiced routine. My mom or dad drove me half an hour to the complex; I snuck through the entrance, reliably late. The class would already be sitting in a circle, everyone’s homework pieces tessellated across the floor, and it would be too late to lay mine down with the gift of anonymity; instead, shame pulsated quietly in my body. Everyone would see which paintings belonged to me, ones I was always certain were inadequate. Homework could range from instructions to design sixteen creative compositions representing Radiohead’s “Everything In Its Right Place” (one of the few songs Fang considered real music, alongside Chopin’s nocturnes), or to produce 100 watercolor sketches of pedestrians. “You are not committed enough,” Fang would say, as I laid down only a third of the demanded, to which I would respond that I was already in over my head—I was trying my best—I had schoolwork, and robotics, and sports, and choir, and other things to manage. “Art is more important than any of that,” he would respond. “One day, you’ll understand. Everything comes from art.” How pretentious.

Summers, balmy as they were in Cupertino, were tropical within the confines of the studio. The forty or fifty of us, crammed side by side at tables meant for far fewer, acted as honeybees, packing our body heat into the hive, wings vibrating against a constant backdrop of scratching on paper and conversation. For weeks, we shared a routine: arrive each day at 9am, spend two hours in critique of the previous day’s work, spend two hours listening to Fang’s lecture, then work on our own pieces until dusk. Our parents took us home, where we continued homework alone until our bodies demanded rest, then repeated it all the next day. At lunchtime, Ms. Zhou would place a bulk order from the Chinese restaurant nearby. Accepting continuous criticism was a task that worked up a ravenous hunger, and we crowded eagerly around the delivery to discover what treasures awaited us. There would always be rice or noodles, along with two portions of tomato scrambled egg, stir-fried beef with bamboo shoots, fried fish, steamed cabbage, or curried eggplant. We were told to cut off and save the square tops of our styrofoam takeout boxes; they could be etched later to make prints. Occasionally; Ms. Zhou led us instead to the KFC across the street. This was a luxury. For years, I had passed by the halo of the Colonel while leaving the studio, but my family didn’t believe in fast food. So in that Cupertino KFC, I tried fried chicken for the first time in my life and learned the glorious, flaky truth of buttered biscuits.

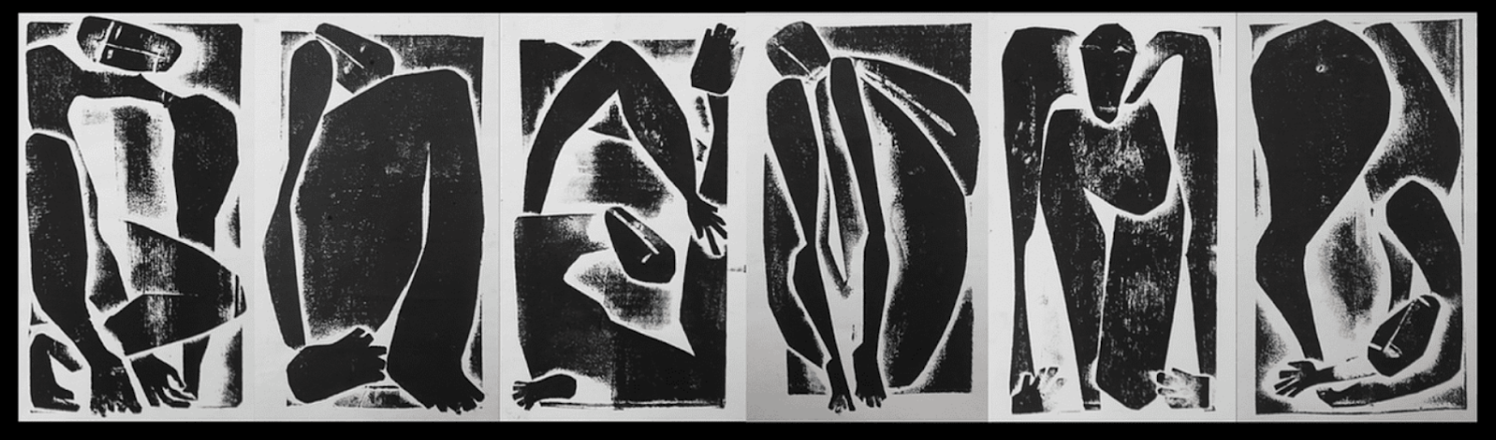

One of the pieces I made during camp. I created these prints by carving my composition from cereal boxes and layering them to create the desired effects in negative space, then pressing them with ink.

It was during those summers, when we partook in long days of art camp, that I got to know the many interesting people of the studio. Despite being a generally well-behaved child myself, I got the sense that I had fallen in with the rebels and rabble-rousers. [redacted] was a couple years older than me. Her hair was always clumped with sweat and grease, and she never arrived at the studio with any materials of her own. She operated on her own hours, sometimes inexplicably disappearing for hours, then producing a masterpiece—when she chose to appear—from paint and paper a wealthier student had given her. Sometimes, she was simply in the bathroom; other times, she had hitched a ride with an unknown man to another city. In one of her reappearances, she returned with a rustling lump under her shirt. “I got it from the trash bin,” she explained, procuring a large, docile raven.

[redacted] and [redacted] were twins from Saratoga whose regular arguments once escalated into a fight with x-acto knives. Blood from their arms smeared across their drawings. Fang scarcely reacted, except to offer band-aids. [redacted] could usually be found scowling under her Balenciaga hat or complaining about her useless fob brother and useless friends. [redacted] was one of the younger boys; the only thing I remember of him was his insistence on pronouncing Gina’s name like vagina. [redacted] had recently come out and enjoyed loudly discussing the various women at school she was sleeping with. [redacted] sat with his mom, who breathed over his shoulder and scolded him for each “incorrect” line he drew. [redacted] and [redacted] dreamt of becoming software engineers.

As I got older, Fang adjusted the topics I studied. I practiced clear expression of ideas and learned to master realism in graphite, charcoal, ink, and acrylic. Then, we veered sharply toward abstraction. I protested—I wanted my beautiful flowers and pastoral landscapes; Modigliani’s portraits appeared disfigured and Matisse’s paper cuts didn’t seem to follow any reason. I learned compositional principles by analyzing something so apparently simple as placing a single line, building toward complex scenes. I could not appreciate the contemporary and abstract at that time, and I shared many of the most common complaints I now hear: many paintings didn’t look like anything in particular, they looked random at times, and certainly not beautiful like gardens and seashores. But I decided to take a leap of faith. I tried to walk with the colors. I tried to listen to the lines. Kandinsky, famously, spent much of his life developing theories of color, shape, and their inherent qualities—I take a more relativistic stance, but the colors and shapes did begin to take on intense emotional qualities. Eventually, I found myself entranced by an ethereal quality that emerged when they combined in just the right ways.

Kandinsky’s “Composition VII,” one of my favorites of his work.

I found myself chasing the novel and unexpected. To look at a piece that felt entirely unknown to me brought a rush of delight; it was like being born anew and introduced to all that lay in this new world. I became confused, I became curious, and I started to wonder. And that, too, is part of art’s magic—wonder, like health, is a resource which is often abundant at birth and becomes scarcer over time. Art is necessary for living because wonder is necessary for living. What is expected does not provoke thought the way something unexpected can, because it does not provoke the surprise that leads to questioning that leads to wonder. It rarely makes me feel something new, which is that sudden revelation that I am understanding something I have never understood before, and that I am understood in ways I never knew I desired. I realized, also, that the farther we stray from realism, the more space is created for viewer and artist to sit together, and in doing so, become collaborators. It is also why we appreciate the subtle and the unsaid in literature: more than anything else, we are fascinated with ourselves. The artist suggests; we fill in our own experiences; in that way, the art is mine; the one work blossoms into a thousand, for its dialogue with each beholder is unique.

I became obsessed with form. I saw shapes everywhere. I could not look at anything without immediately seeing its art. To the practiced eye, the distinction between reality and art disappears. My favorite things became simple. I was content to lie on my stomach, observing the linens—each curve and crease unique, how gently the light shaded some areas and how dramatic was the contrast between others—the lines folded into themselves, like great northern waves cresting and falling, frozen in their warring postures. So the simple became divine. Overgrown weeds danced ballet. Chairs’ shadows sparred beneath stage lights. Alstroemerias wilted, posed, begged, each unique in its dying gift. The ephemeral, the everlasting, the mundane, the inimitable! Dust became stars before my eyes. Were the works of Pollock not in the criss-crossing of branches above; were the illusions of Frankenthaler not replicated in the undulating prints of curbside ice; were Kandinsky’s carnivals of color not in the shifting brown and green and amber and cobalt of murky pondwater, so intensely vermilion in those glints of light?

I had a sense then that my consciousness was groping for something sweet, hurtling toward a place from which I could never return. I was utterly hypnotized. A protective film had fallen from my lens; my world became vivid; it buzzed with constant anticipation of discovery. It is impossible to describe the feeling of that trance state. And perhaps I should stop trying; after all, Edward Hopper agreed that “if you could say it in words, there would be no reason to paint.”

If you could say it in words, there would be no reason to paint. If you could say it in words, there would be no reason to sing. If you could say it in words, there would be no reason to use words, even—that is, words liberated from their assigned roles.

In this way, as I was liberated from the confines of traditional artistic beauty, so too was I liberated from the need for music that “sounded good” and from the allure of literary drama. I love plenty of music that most would agree “sounds good”—Verdi, Laufey, Kendrick Lamar—and I don’t intend to discredit music that is popular or catchy. But what does it mean for a song to “sound good”? Often, it is familiarity. For example, in Western musical tradition, we tend to use the twelve-tone scale, favor intervals like the third, the fifth, and the sixth, and use repetition to recall themes within a work. The I-IV-V-vi chord progression characterizes thousands of pop songs. But when I performed the exercise of deconstructing music to its basic elements—as Fang once had me do with colors and lines—all I found was sound. Sound that required no rules, that could divide the octave into more intervals, that need not be instrumental, that could be uncomfortable. By attempting to limit “song” with any kind of convention, we dull its most flexible power to simply tell story through sound. I wanted to hear and make music that called me into the world of dreams. I wanted to be shown what I had overlooked. I wanted to read and write poetry that tore me from the earth and then sent me back. I wanted absurd expression to recognize this absurd reality.

I realized, too, that all these art forms are inextricably connected. Language is sound. What are words but units of music, sentences but melodies? Kandinsky’s paintings conjure symphonies. Every painting is coursing with rhythm and harmony and overflowing with silence. It is all quite synaesthetic, because it is all just an experience of deep noticing, and then of trying to fit those emotions—often more intensely true than their original experience—into imperfect vessels.

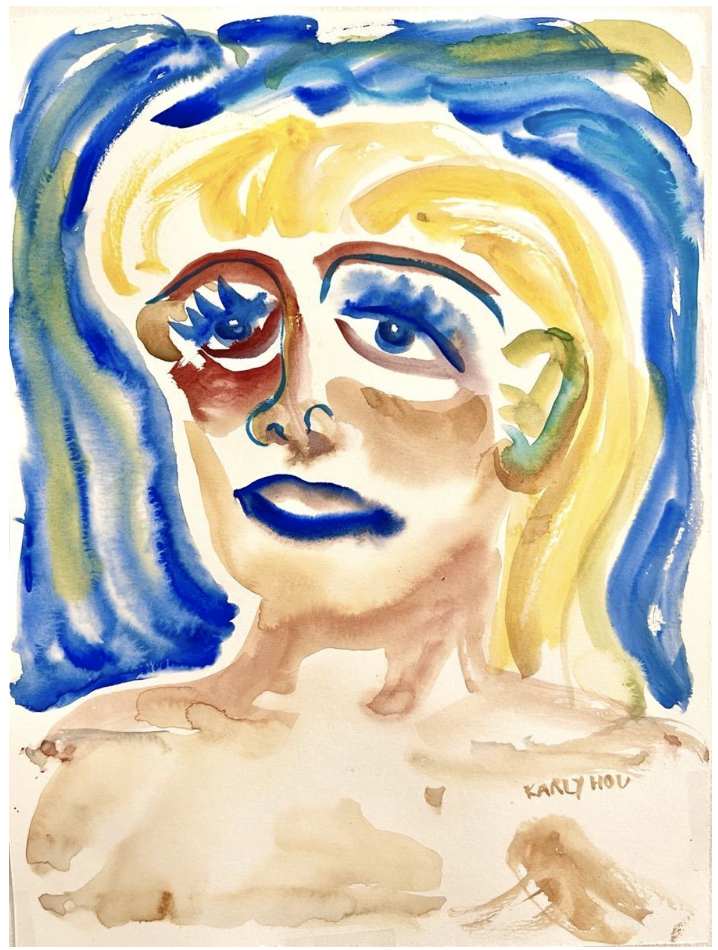

A watercolor sketch I did last summer.

It is impossible to describe the feeling of being in that trance state, but maybe it is this: that I feel closer than ever to my humanity, as if I were standing on the marshy banks of the finite and ephemeral, gazing into the warm abyss of the infinite and divine. That many things we encounter in our lives are means to something else, and as means, thus unsettled, insatiable, and requiring justification, but I have found something that is an end in itself, unjustifiable, and uniquely valuable in its unjustifiability. That my individual experience is deified, and reaching out to be received by another, but even if it were not, it would have value simply in existing. That I question whether I have constructed an artificial state of mania, of insanity, and chosen to reside within it regardless. That I long constantly for it and can no longer bear to live outside of it for too long at a time. That I cannot show it to anyone who has not felt its transformation, only say that it is worth finding.

Maybe it is this: that it is like religion. I did not grow up religious, but the experience of faith seems to move in parallel directions. How did religion come to be? Many theories exist: some say that our ancestors saw lightning and did not know how to explain it, that they saw life and death and needed a way to accept it. But I think it is possible that someone once heard a song, and sat the way I am sitting, eyes glazed and staring into the stars.

Having visited the spiritual world, it became impossible to live solely in the material one. What material pleasures could rival the existential kind?

Last summer, I stood before the Whitney’s Kuniyoshi painting “Deliverance,” my face far too close to the canvas for the security guard’s liking. It was ecstasy. I reached for my phone to text Fang. I hadn’t spoken to him since high school. I wanted to tell him that he was right. That it had taken me over a decade, but I finally understood, or thought I did, at least. Instead, I sent him a picture of the painting.

I saw this today, I typed. It reminded me of you.

Kuniyoshi’s “Deliverance.”